The person who smoked a pack a day may have moved out years ago, but the toxic substances left behind stuck around. And to this day, the particles that settled deep into furniture, carpets–even the drywall–remain available to be picked up and adsorbed by growing children.

In fact, more than 95% of children living in homes considered smoke-free carry detectable levels of nicotine on their hands, which means a stew of thousands of toxicants found in tobacco smoke is finding its way into growing kids even though parents are trying to keep the smoke out. That’s the surprising new finding about thirdhand smoke published Feb. 7, 2022, in JAMA Network Open, by researchers at Cincinnati Children’s and San Diego State University.

No level of exposure to tobacco pollution is considered “safe” for kids. Discovering that smoke residue is widely detected among children even in homes thought to be smoke-free was a deep surprise even to the scientists.

“We had performed a similar study involving kids from smokers’ homes, and as we expected, we found nicotine on nearly all the kids’ hands. In this study, we expected the exposures in smoke-free homes to be near zero, but they were not,” says Melinda Mahabee-Gittens, MD, MS, a member of the Division of Emergency Medicine at Cincinnati Children’s and a long-time researcher of the impact of tobacco pollution exposure.

Mahabee-Gittens oversaw the medical testing of children in this study and leads a clinical trial that seeks to enroll 1,000 children in the Cincinnati region to further study this issue. Ashley Merianos, PhD, an assistant professor of health promotion and education at the University of Cincinnati was a co-author.

Samples collected in Cincinnati were sent to San Diego for analysis. The corresponding author for the paper is Georg Matt PhD, a member of the Department of Psychology at San Diego State and Director of the Thirdhand Smoke Resource Center, founded in 2011.

“This is the first part of a much larger study (of which Dr. Mahabee-Gittens is the PI) that looks at clinical outcomes. We are publishing the first part because it was so stunning how widespread the exposure issues are,” Matt says. “To me it was a surprise how widespread this pollutant is, even in communities with low smoking rates and even in homes where nobody has smoked for years. This is a really long-term, persistent and pervasive pollutant.”

What is Third-Hand Smoke?

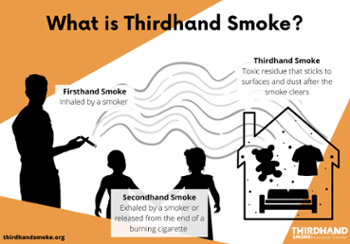

Many people know about secondhand smoke and recall the role studies from decades ago played in driving a wave of indoor smoking bans from government buildings to restaurants and bars. Now, the less-studied role of thirdhand smoke exposure is coming to light.

Firsthand smoke directly affects the person smoking. Secondhand smoke involves all people who wind up inhaling someone else’s smoke. Thirdhand smoke refers to the particles that settle out from the exhaled smoke and coat surfaces, which can be picked up, ingested, or inhaled later by anyone but pose the highest potential risk to children.

A library of previous studies has documented the complex mix of toxic chemicals found in tobacco smoke residue. Much also is known about how the various chemicals can affect the human body. But relatively few have connected potential health problems with the smell of a house or car that has been coated and re-coated with smoke residue.

In children, thirdhand smoke exposure can increase risk of respiratory and infectious illnesses, including asthma, bronchiolitis and pneumonia. Compounds within thirdhand smoke also are known to be genotoxic, which means they can damage the DNA within the cells of exposed tissue.

“This thirdhand smoke mixture is such a potent mixture of different compounds that it can literally affect all organ systems,” Matt says. “That’s why we are particularly concerned about children as their organ systems are still developing and their body’s defenses are not as well developed as in an adult.”

In the home, or in a car, or any place where smoke residue has settled, children who were not present while adults were smoking can absorb toxicants from tobacco pollution in multiple ways. They can ingest particles by getting the residue on their fingers, then putting their fingers in their mouths—a common childhood behavior. They can inhale old particles through a process called off-gassing. Children also can absorb some of the thirdhand smoke chemicals directly through the skin on their hands.

Much like polluted dust carrying old bits of lead paint, the residue left behind by tobacco smoke does not evaporate or decay quickly into harmless materials. It lingers until it is wiped up, washed out, or otherwise removed.

“In a previous study, we detected thirdhand smoke in the home of a non-smoker eight years after their spouse, who was a smoker, had passed away,” Matt says.

What does the new study reveal about Thirdhand Smoke exposure?

Sharp disparities exist along economic lines for children exposed to thirdhand smoke.

This study looked at data from 504 children all of whom were tested at Cincinnati Children’s. The team determined that 311 of the children lived in places considered “protected” from smoke exposure, while 193 were living in “exposed” conditions.

As expected, nicotine was found on the 98% of the children living in exposed conditions. However, nicotine was also found on 95% of children in “protected” spaces.

Overall, testing found about 3 nanograms per wipe among children in non-smoking homes, which unsurprisingly was lower than the 22 nanograms per wipe found on children in smoking households.

However, even though nonsmoking families believed they were living in smoke-free homes, children in the lowest income families (less than $15,000 household income) had 14 nanograms per wipe. Children from the highest income homes (above $120,000) were found to have less than 3 nanograms per wipe.

In smoking households, testing found about 45 nanograms per wipe among children in the lowest income homes compared to about 4 nanograms per wipe among the highest income households.

This means that some low-income children living in homes thought to be smoke-free had at least as much tobacco pollution exposure as higher-income children living with active smokers.

“This study is another example of income-related health disparities,” Matt says. “The people with the least resources are also least able to afford newly built smokefree housing, the least able to replace old smoke-embedded carpets and couches with new ones, and the least able to influence what neighbors do in multiunit buildings or how landlords maintain them.”

How risky might Thirdhand Smoke exposure be for kids?

So how serious is the risk?

“We don’t know for sure yet. In a recent publication we had that looked at smokers’ children, we found that the levels of nicotine on these children’s hands were associated with respiratory illnesses and infectious illnesses,” Mahabee-Gittens says. “These kinds of risks had been previously thought to be associated with secondhand smoke. Now we have an ongoing study looking at thirdhand smoke. We’re looking at a variety of clinical patterns to further explain what these hand nicotine levels mean for non-smokers’ kids.”

However, Matt and Mahabee-Gittens emphasize that no level of exposure can be considered safe.

Time to update public policies?

Laws regulating smoking in America vary from state to state, city to city. Only some jurisdictions have taken actions based on concerns about thirdhand smoke exposure.

For example, many local governments prohibit smoking in family childcare homes when children are present, but California prohibits any smoking in a building used as childcare home, even if that building is a private home. Few other jurisdictions do the same.

“A few years ago, California passed a law that makes it illegal to smoke in a car while children are in the car,” Matt says. “That was a concern about secondhand smoke. But now that we know about thirdhand smoke, people should not be smoking in cars at all.”

Political support for smoking bans ranges widely across the nation, and within California. But the Thirdhand Smoke Resource Center has found one aspect of apparent common ground. The center’s polling data indicates that many people support disclosure requirements for real estate sales and rental agreements.

“Nine out of 10 inquiries we get at the resource center here are from people about to buy a home or who just bought a home or a car, and then they find out there’s this funny smell.” Matt says. “We’ve been involved in lawsuits where buyers have sued over lack of disclosure.”

Many paralleles with lead-paint pollution issues

If the concerns about how to mitigate toxins in tobacco smoke dust sound similar to the nationwide debates and reforms related to lead-paint exposure, they should. The dust particle exposure pathways are similar. The toxic compounds can linger for years. And clean up can be both difficult and expensive.

“The big difference is that you cannot buy lead paint anymore. People still smoke, so the smoke pollution is ongoing,” Matt says.

For many, one surprising intersection between old paint dust and thirdhand smoke residue is that both pollution sources cause lead particles to get inside children.

“So not all of the lead that one finds in multiunit housing is from lead paint or from times when lead was in gasoline. Some of the lead we have found in homes here in San Diego comes from tobacco smoke residue,” Matt says.

And that can mean expensive efforts to mitigate lead paint can be undermined over time by ongoing indoor smoking.

Few quick fixes on the horizon

In a nation riven by political division, it will likely take years to see community-wide actions to address lingering thirdhand smoke.

“We live in an environment that is coated with this legacy of tobacco use,” Matt says. “All we can do is raise awareness and make sure people understand what they are doing. It’s not just a harmless unpleasant odor, it’s a potent mixture of pollutants that you should not expose your children to.”

How can families protect children from Thirdhand Smoke?

“If you have children, it’s great if you don’t smoke in the home around children. But you should really have a broad, strong smoking ban,” Matt says. “Don’t even smoke outside if your children are around, and never smoke indoors. Indoor smoking is just a terrible idea.”

Even if policy changes remain distant, there are steps individuals can take:

- Make sure you have a strict smoking ban in your home—and your car

- Control dust by regularly wiping surfaces. Use vacuums that have HEPA filters

- Frequent washing with regular detergents will remove thirdhand smoke residue from toys, clothing and bedding, but not carpets and old couches.

- Avoid hand-me-down furniture

- Replace old carpet; steam cleaning is not effective as a long-term treatment.

- If you live in multiunit housing, learn and seek enforcement of building smoking policies

- Advocate for smoking bans in your building

- When moving, ask about the smoking history of potential new residences.

“If you are living in a home where you know people have smoked, it would be good to find out more. Was this really a home where someone smoked a pack a day for the last 20 years? If that’s the case, I personally would move out,” Matt says. “But not everyone has that choice.”

What's next?

Mahabee-Gittens is leading a clinical trial that seeks to enroll another 400 children mostly from non-smoking homes to learn more about how health measures vary across differing levels of thirdhand smoke exposure. The total to be enrolled will be about 1,000 children.

To learn more, send an email to healthyfamiliesstudy@cchmc.org or call 513-218-0517. Participants can receive up to $245 for completing the study.

MEDIA CONTACT

Tim Bonfield, timothy.bonfield@cchmc.org

- Sharing Many Children Still Exposed to Tobacco Smoke Pollution Even in ‘Smoke-Free’ Homes using Facebook

- Sharing Many Children Still Exposed to Tobacco Smoke Pollution Even in ‘Smoke-Free’ Homes using Twitter

- Sharing Many Children Still Exposed to Tobacco Smoke Pollution Even in ‘Smoke-Free’ Homes using Email">

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA